You’ll notice I talk about the capital-T Tax a lot — teams straining to stay under it, maneuvering to trim their bill, charging aggressively over it, or sketching out future pathways to get back below. That’s not just a personal fixation. The Tax is one of the clearest reference points we have for predicting future transactions.

Here’s a quick NBA Tax primer, and why it matters when owners decide to save money.

The NBA Tax System

The NBA’s tax line sits at 121.5% of the cap (rounded to the nearest thousand). If your end-of-season Team Tax Salary exceeds that line, every dollar above it triggers a progressive tax (think, federal income tax). The deeper a team goes into the tax, the harsher the rate per dollar.

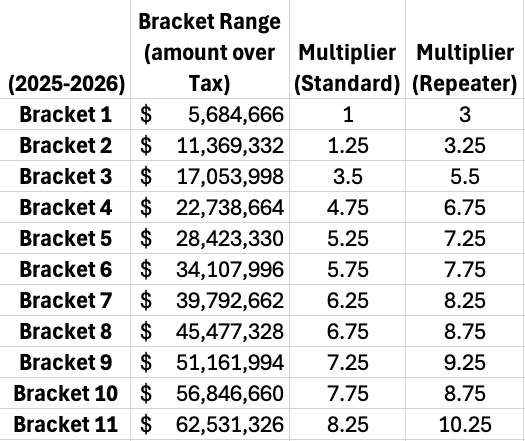

Starting this season, the multiplier penalties get steeper:

Team Tax Salary

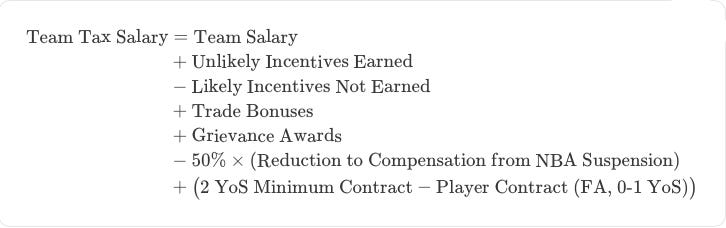

So, if your Team Tax Salary exceeds the Tax Level, you pay these tax multipliers. What is Team Tax Salary?

Tax Team Salary is defined fully in Article VII, Section 2(d)(1)(i) of the CBA. In practice, the calculation looks like this:

The big inputs to track here are:

Cap Hits (Included in Team Salary (base salary/guaranteed amount/likely incentives))

Likely Incentives (included unless later not earned)

Unlikely Incentives (excluded unless later earned)

Minimum Contract Years of Service Variance Amounts (if any, these aren’t necessarily common)

The rest — trade bonuses, grievance awards, NBA suspensions — tend to emerge throughout the season and are generally treated as risk exposures rather than baked into the initial projection.

Team Tax Salary is calculated at the end of a season. Generally, the last opportunity to make a big change in salary is the trade deadline.

The Tax Distribution

So, if your Team Tax Salary is above the Tax Level, you pay all this extra money. Where does all this extra money go?

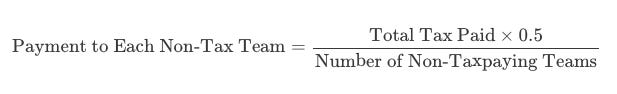

For that, we look to Article VII, Section (2)(d)(4)(i):

[T]he NBA may elect to distribute up to fifty percent (50%) of such amounts to one (1) or more Teams based in whole or in part on the fact that such Team(s) did not owe a tax for such Salary Cap Year (e.g., subject to Sections 2(c)(2)(ii) and 2(c)(7) above, the NBA could elect to distribute fifty percent (50%) of such amounts in equal shares to all non-taxpayers in such Salary Cap Year);

While the CBA uses somewhat curious instances of “may” and “could,” the common practice is for the League to distribute 50% of the Tax payments to the non-taxpaying teams in equal shares.

For a given year, you can project this payment with the following formula:

Why Ducking the Tax Makes So Much Sense

For teams, crossing the tax line is a net cost decision: ownership and the front office have to weigh the projected tax bill plus the opportunity cost of forfeiting the league’s tax distribution.

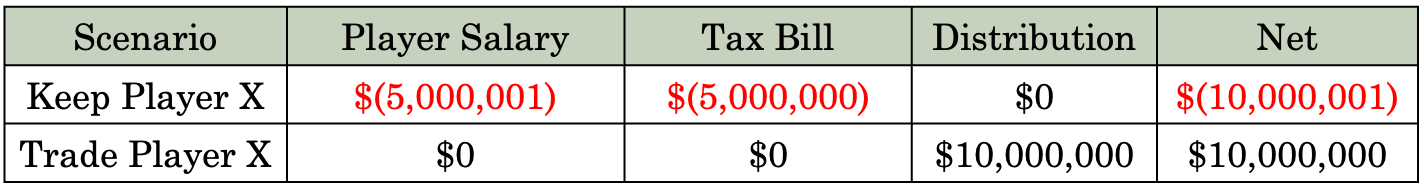

A Hypothetical

Take Team A. With Player X on the roster, they project to finish $5 million over the Tax Level. If they trade him away without taking salary back, they can sneak $1 under.

Here are the two decisions for that team:

All in, the “cost” of keeping that $5 million player isn’t just paying him his $5 million salary. It isn’t even just paying his $5 million salary and paying the $5 million tax bill. It’s those things + the lost $10 million distribution. A $20 million swing, in total.

Repeat Taxpayers

This decision is amplified for repeat taxpayers. Under the CBA, any team that finishes above the luxury tax in three of the previous four seasons is designated a repeat taxpayer and pays elevated rates (see the tax rate table above). Of course, this inflates the “Tax Bill” part of our hypothetical decision above, making it even more desirable to avoid the Tax.

Who Looks to Duck the Tax

Well, everyone. All things equal, a team is better off not paying the Tax than paying it. The general exceptions are the true contenders (it’s worth spending a premium to contend) and the ownership groups with so much money that the above hypothetical doesn’t really resonate (it’s not worth potentially sacrificing on-court value for so little).

Why Luke Cares About Whether Owners Save Money

I don’t really care if owners save a few million here or there. What I care about is what this money means for how teams are run. If an owner cares about saving this money, then the front office cares about saving this money. If the front office cares about saving this money, then that changes the types of transactions they’ll pursue.

If a team is just over the tax line, you can expect them to make a trade (or series of trades) to get just below it. If a team is below the tax line, you can expect them to make a trade (or series of trades) to get as close to the line as possible without going over.

To show how this plays out in practice, here’s a look at how each team’s 2024–25 tax position shifted from the start of trade season to the end:

I think of this as the in-season tax room redistribution. The teams sitting a few squares above the Tax line look down the board at the teams with empty squares and say: “Hey, take my squares into your empty squares and I’ll pay you for the trouble.”

The 2025-26 Tax Landscape

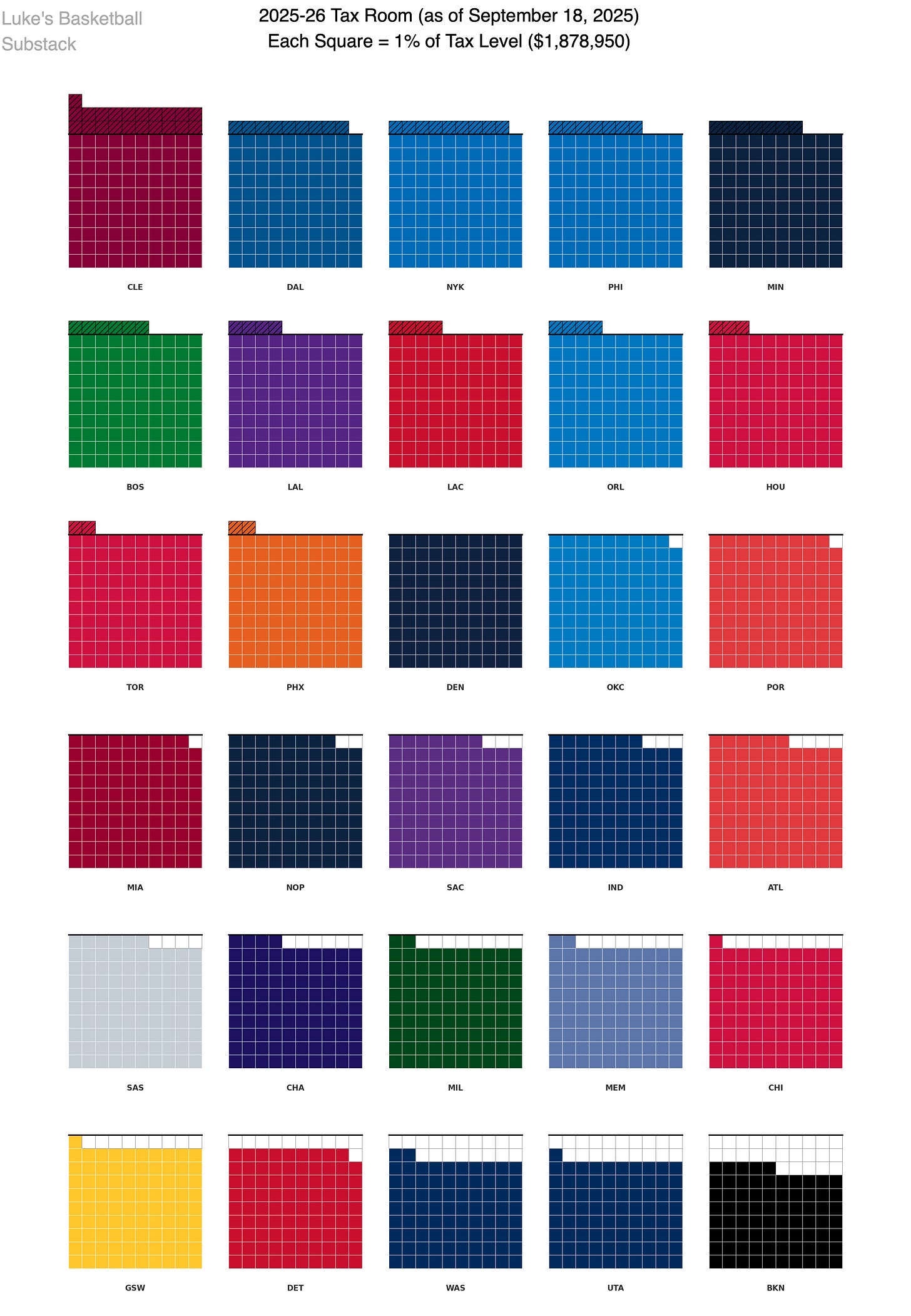

Here’s a look at this season’s current landscape:

*note from Luke in the future: I realized this visual contains a projection for Quentin Grimes for PHI. They are actually just below the Tax as of this date.*

Here’s what you can expect:

Golden State will likely climb above the Tax once they finish sorting out their offseason moves.

Teams sitting a few squares above the line can be expected to maneuver down and get below.

Teams with open squares below the line are positioned to take on salary from those over the line (and to pick up future assets as payment for doing so).

I’ll keep updating this Tax Room visual as the season unfolds. It should give us a pretty good sense of where the natural trade partners are.